Judy Hashman, legend, author of multiple records, died earlier this week, on Monday 6 May aged 88.

The records are there in black-and-white: 10 All England women’s singles titles (the highest ever); seven All England women’s doubles titles, a dozen US Open singles titles. Third on the all-time list of All England winners. Three-time Uber Cup winner. Inductee into the IBF Hall of Fame (1997) and the International Women’s Sports Hall of Fame (1995).

What made Hashman the greatest badminton player of her era and among the all-time greats?

Of course there was supreme athleticism (she played field hockey, tennis and lacrosse at a high level), and great genes (her father Frank Devlin was a badminton legend, her mother Grace a Wimbledon tennis player); additionally, there was the mental ability to control the game and blank out everything but the moment.

In the words of ‘Mr Badminton’ Herbert Scheele – legendary administrator of the game and editor of Badminton Gazette and World Badminton – “she attracted the lines to her shuttle.”

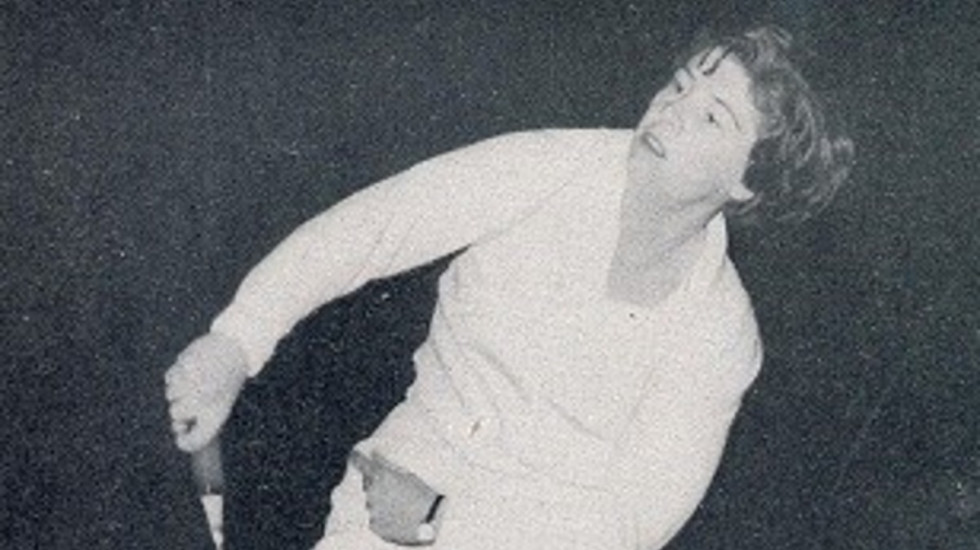

Sisters Judy and Sue Devlin (right).

That kind of control wasn’t easily achieved, particularly in the days of amateur badminton. Having grown up in Baltimore, USA, as the daughter of the great Frank Devlin, Judy recounted the limited time she and her older sister Sue had for the sport when they were in college. They had barely an hour a day for practice, so the mind had to be fully focussed. It was this honing of the mind that served her well, helping her made 10 straight All England singles finals between 1954 and 1964.

“I was going to university and studying, and I had very little time,” Hashman said, of her playing days in the US, before her marriage and relocation to the UK in 1960. “I was either playing badminton for one hour a day or studying… and I was usually so tired by the time the tournament came… we drove eight hours through the night to get to one tournament (Canada Open), and on the Sunday evening after the finals, we drove right through the night, got home at about 7 in the morning, had a shower, and went to work, or went to teach.

“Everything was so far away. There was no big tournament in the place where we lived. It was either Washington which was the closest, or Philadelphia, or Boston, or Toronto. You’re exhausted even when you arrive, so I had to develop concentration, how I can keep my mind going. I had trouble knowing what the score was, because I was just on that point. Every single point, I said, ‘Get this point’. I had to be on the actual action, concentrate, and that stops you from being tired.”

The Devlin sisters with their father Frank (2nd from right) during a TV show

Badminton’s gain was tennis’ loss. Hashman was an all-round athlete growing up – she was picked for the USA junior tennis team, and she was also a field hockey player and a member of the national lacrosse team. But she chose badminton.

“I can just remember saying that’s the sport I want to play. They were all amateur sports. I got offered to give up all sports and play only tennis at age 16, and I said no. It just didn’t interest me to that extent. Tennis is very slow, you have a lot of time in between to fret. Badminton is much quicker, the brain has to keep working all the time, there’s no resting. It appealed more to me. You had no time to self-doubt. Once the rally is over you have to look at the next one immediately. You don’t have time to wander around the court and bounce the ball – you just have to get on with it. Temperamentally badminton suited me that way.”

Hashman’s one regret was that she could never be a full-time player and thus discover how much more she could have accomplished. Yet, with the approach of a professional in a period of amateur sport, Judy Hashman was ahead of her time.